Shorebirds: can we do more to protect them?

By Neil Fraser, Tomaree Birdwatchers.

This is the third article in my series on the shorebirds of Port Stephens. Previously I described some of the local migratory and endemic shorebirds, and the incredible journey made by the migratory species that grace our shores in summer. This article briefly summarises the legislative framework and international agreements which provide protection for shorebirds and looks at their conservation status. Some of the key threats are discussed as well as the measures intended to protect their habitat.

Our threatened migratory and endemic shorebirds

The conservation status of migratory and endemic shorebirds that have been recorded in Port Stephens are shown in the table below. Some of the smaller species, Lesser Sand Plover, Terek Sandpiper, Great Knot and Sanderling have not been recorded locally for some years. For some species the assessed status varies between the State and Commonwealth reflecting differences in population trends nationally and for individual states. The Little Tern, another migratory species, is also included in the table although it is not a true shorebird. It nests on secluded beaches in Port Stephens in summer.

Species name | Commonwealth status | NSW status | |

Migratory species | |||

| Lesser Sand Plover | Charadrius mongolus | Endangered | Vulnerable |

| Black-tailed Godwit | Limosa limosa | Vulnerable | |

| Bar-tailed Godwit | Limosa lapponica | Vulnerable | |

| Far Eastern Curlew | Numenius madagascariensis | Critically endangered | |

| Terek Sandpiper | Xenus cinereus | Vulnerable | |

| Great Knot | Calidris tenuirostris | Critically endangered | Vulnerable |

| Red Knot | Calidris canutus | Endangered | |

| Sanderling | Calidris alba | Vulnerable | |

Endemic species | |||

| Beach Stone-curlew | Esacus magnirostris | Critically endangered | |

| Australian Pied Oystercatcher | Haematopus longirostris | Endangered | |

| Sooty Oystercatcher | Haematopus fuliginosus | Vulnerable | |

Other species | |||

| Little Tern | Sternula albifrons | Endangered | |

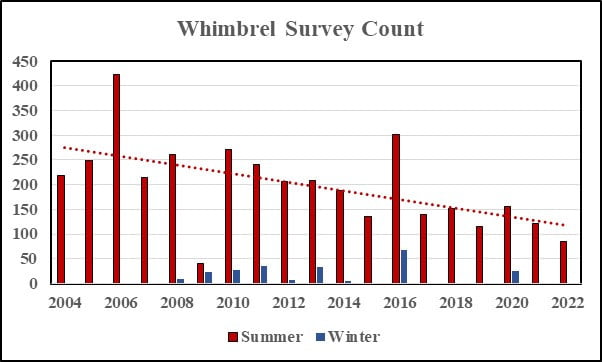

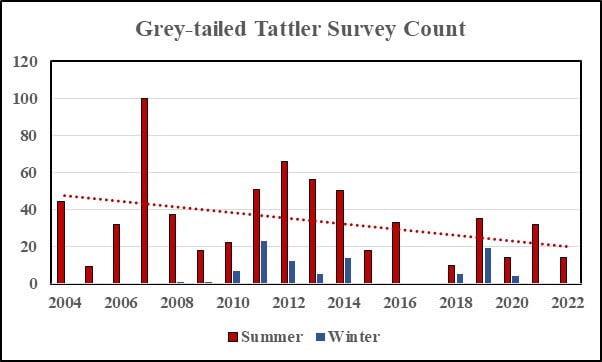

The declining population trends for Far Eastern Curlew and Bar-tailed Godwit, both of which are threatened, were shown in the first of my shorebirds series. However, population decline is also evident for some species that are not currently listed as threatened. Charts of survey counts and population trends from bi-annual surveys in Port Stephens conducted by the Hunter Bird Observers Club (HBOC) are shown below for Whimbrel and Grey-tailed Tattler. Beach Stone-curlew has been expanding its range southwards along the NSW coast since the early-1980s and first appeared in Port Stephens in 2006. There are currently two breeding pairs known in Port Stephens.

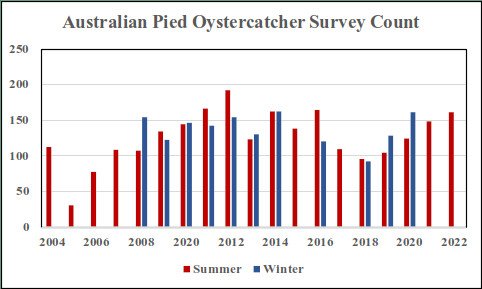

While the populations of some species of migratory shorebirds are declining, the good news is that the populations of the endemic Australian Pied Oystercatcher and Sooty Oystercatcher appear to be increasing.

NSW legislation

In NSW, the key pieces of legislation that identify and protect threatened species, populations and ecological communities is the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and its regulations. The NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee determines which species, populations and ecological communities are listed as critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable under this Act.

In NSW, threatened species are managed under the Save our Species (SoS) program which is stewarded by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). The objectives of SoS are to increase the number of threatened species that are secure in the wild in New South Wales for 100 years and control the key threats they are facing. More than 11,000 species and threatened ecological communities have been identified at risk. Over 100 key threats are being addressed with more than 400 projects underway across over 850 sites. The SoS program is implemented through the combined efforts of volunteers, scientists, businesses, community groups and the NSW Government working collaboratively. The NSW Scientific Committee decides which plants, animals and ecological communities are listed as threatened.

In the Port Stephens area, shorebirds managed under the SoS program are Little Tern, Great Knot, Greater Sand-plover, Lesser Sand-plover, Black-tailed Godwit, Terek Sandpiper and Curlew Sandpiper.

The NSW Local Land Services (LLS) also delivers Natural Resources Management (NRM) and Biodiversity Programs that support native flora and fauna recovery and conservation programs to protect threatened species, threatened ecological communities and Ramsar wetlands. Programs are run in close partnership with a range of regional stakeholders and partner groups.

In Port Stephens, LLS has funded a project directed at improving saltmarsh habitat and reducing threats to the Far Eastern, Little Tern and Gould’s Petrel. Signs supporting protection of local migratory and endemic shorebirds have been installed around our local shores. Birdlife Australia prepared the Port Stephens Estuary Shorebird Site Action Plan for this project. A recommendation of the plan was to establish a Port Stephens working group for migratory shorebirds modelled on the Manning Beach Nesting Birds Working Group to implement the plan.

Commonwealth legislation

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) is the Commonwealth Government’s environmental legislation. It covers environmental assessment and approvals, protects significant biodiversity and integrates the management of important natural and cultural places.

The Act is focused on matters of national environmental significance, which are based primarily on Australia’s responsibilities under international agreements on environmental protection. Four matters of national environmental significance that offer some measure of protection to shorebird species are the listed threatened species and ecological communities, migratory species protected under international agreements, Ramsar wetlands of international importance and world heritage properties.

An independent 10-year review of the EPBC Act headed by Professor Graeme Samuel released in 2020 found the Act has failed to achieve its objectives and needs a complete overhaul.

‘It should be re-written into a new Act or Acts. The report states: Australia’s natural environment and iconic places are in an overall state of decline and are under increasing threat. The environment is not sufficiently resilient to withstand current, emerging or future threats, including climate change. The environmental trajectory is currently unsustainable. The EPBC Act does not clearly outline its intended outcomes, and the environment has suffered from two decades of failing to continuously improve the law and its implementation.‘

The newly-elected Labor Government has committed to implement the findings of the review.

Our international agreements

For over 30 years, Australia has played an important role in international cooperation to conserve migratory birds in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, entering into bilateral migratory bird agreements with Japan in 1974, China in 1986 and, most recently in 2007, the Republic of Korea. Australia is also party to international conventions including the Convention on Migratory Species (Bonn Convention), the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Convention), the Convention on Biological Diversity and the East Asian-Australasian Flyway Partnership including relevant working groups and task forces.

These agreements provide for the protection and conservation of migratory birds and their important habitats, protection from take or trade except under limited circumstances, the exchange of information, and building cooperative relationships. Birds listed in these agreements are listed as migratory species under the EPBC Act.

The Ramsar Convention

Shorebirds are most commonly found foraging in intertidal areas or on the fringes of freshwater wetlands. Many of the world’s important wetlands are listed under a global treaty known as the Ramsar Convention which was signed in 1971 in Ramsar, Iran. Contracting parties agree to manage their wetlands based on the concept of ‘wise use’, maintaining the ecological character while allowing sustainable use for the benefit of people and the environment. Under the convention’s listing criteria, wetlands should be selected based on their international significance in terms of the biodiversity and uniqueness of their ecology, botany, zoology, limnology or hydrology. In addition, wetlands of international importance to waterbirds at any season should be included on the Ramsar List.

Today, 170 nations are signatories to the Convention and over 2,300 wetland areas covering 248 million hectares are inscribed on the Ramsar List. Australia became a signatory in 1975 and 66 wetlands covering over 8.3 million hectares are listed. Locally, this includes the Hunter Estuary Wetlands (3,388 ha) and the Myall Lakes NP (44,612 ha) which includes Corrie Island. One of the Ramsar selection criteria states:

‘A wetland should be considered internationally important if it regularly supports 1% of the individuals in a population of one species or subspecies of waterbird.’

As noted previously, Port Stephens supports over 1% of the world population of Far Eastern Curlew and Australian Pied Oystercatcher, thereby justifying listing for part of the area.

However, listing under the Convention does not necessarily protect a site from development. In 2017, the then Minister for Environment, Josh Frydenberg, proposed that part of the Moreton Bay (Qld) Ramsar site be de-listed to allow a proposal by the Walker Corporation for a marina with associated residential and commercial developments to be approved. The area is a key site for the Critically Endangered Far Eastern Curlew and other migratory waders. Despite widespread public protest against the proposal, approval for the development is still pending.

Recently, a submission was made to the Port Stephens Council to support nomination of the Mambo Wetlands Reserve and the Wanda Wetlands for listing under the Ramsar Convention based on the presence of 17 threatened flora and fauna species and 4 endangered ecological communities. Migratory and endemic shorebirds and other waterbirds forage on the mudflats and amongst the mangroves on the adjacent Salamander Bay shoreline at low tide. To date, support has not been forthcoming.

Threats to our birds

Birdlife Australia lists the following as threats to shorebirds in Australia:

- Climate change

- Disturbance from recreational activities – 4WD driving, fishing, jet boats, off-leash dogs

- Extractive industries – fishing, shellfish, seaweed and wrack harvesting

- Habitat loss through coastal development – ports, industrial, residential

- Hydrology change – flood frequency, salinity, acidity and nutrient levels

- Invasive species – animals and plants

- Pollution – agricultural, residential and catchment run-off.

The most significant threats to all birds nationally are from feral animals (predominantly foxes and cats) as well as habitat loss and fragmentation. The impact of these threats locally cannot be accurately assessed. Both foxes and cats are present in Port Stephens and clearing of mature coastal woodland for urban development is continuing, such as at Anna Bay.

The fox is a successful apex predator. In NSW it favours fragmented landscapes and coastal forests where densities are around 1-2/km2. However, in peri-urban and urban areas where food is abundant, densities may be as high as 12/km2. The 2016 Saving our Species program recognised predation by foxes and feral cats as a Key Threatening Process for many avian species.

Last summer, a fox on Corrie Island predated the nests of a breeding colony of Little Tern, causing the birds to abandon the site. Australian Pied Oystercatchers and Beach Stone-curlew also nest on Corrie Island and it is not known if their nesting attempts suffered a similar fate.

Impacts of climate change

The impact of climate change on shorebirds cannot be accurately forecast. However, coastal habitats will be impacted by sea level rises, increased temperatures, and more frequent extreme weather events. The impact of sea level rise within Port Stephens will be significant and the Council is planning for a rise of 0.91m by the end of the century. Large areas surrounding the Port are low lying with 30% of the LGA covered by wetlands.

The area of the estuary and overall water depth will increase with rising sea level, resulting in a larger tidal prism producing higher velocity tidal flows. Estuarine sedimentation patterns and geomorphology will change. More extreme weather events such as increased flood frequency will also impact hydrology and result in changes in salinity, acidity and nutrient levels. Increasing temperatures will result in increased acidification of waters. A loss of tidal flats, seagrass and saltmarsh can be anticipated as well as an impact on the benthic fauna foraged by shorebirds.

Shoreline protection in Port Stephens

Port Stephens is fortunate in having large areas of relatively undisturbed shoreline and adjacent habitat that is protected. All the waters (up to the tidal limits) within Port Stephens are part of the Great Lakes Marine Park. Important habitat areas within the park are designated as Sanctuary Zones or Habitat Protection Zones. The waters entering Port Stephens from the major tributaries, the Myall River, Karuah River and Tilligerry Creek, are unpolluted. There are no major industries or urban centres, and no intensive agriculture along these waterways and much of their catchment is within state forests and national parks.

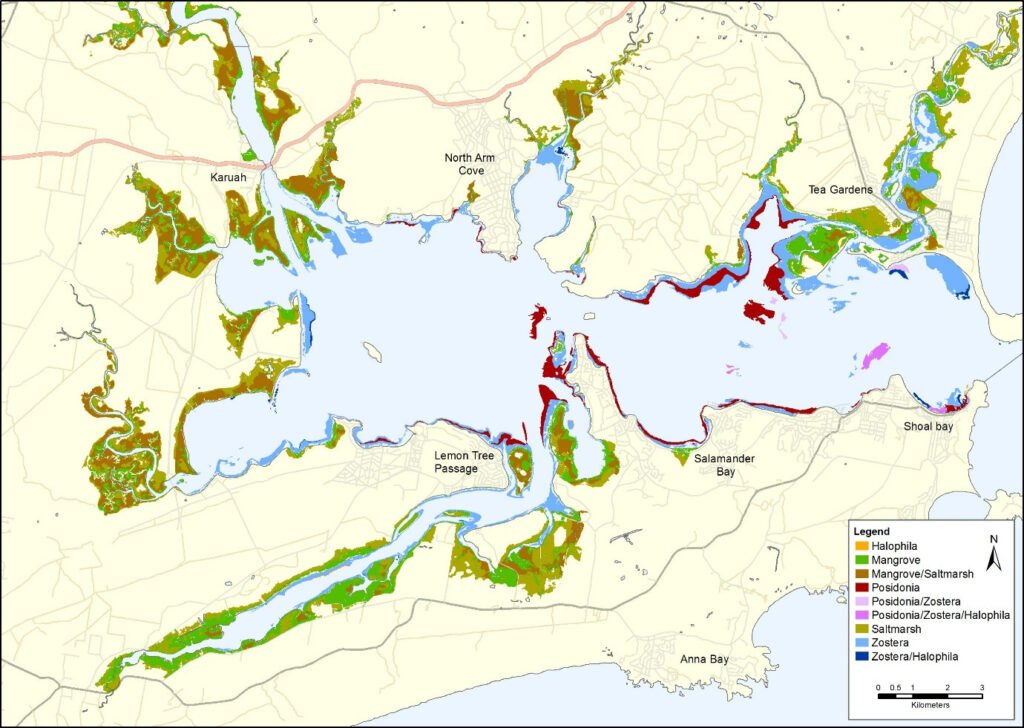

Extent of saltmarsh and mangroves, (olive, green, brown) and seagrass (blue, pink, red) within Port Stephens and its tributaries. Source DPI

Extensive areas of shoreline, the islands and adjacent areas surrounding Port Stephens are protected by national parks or nature reserves. These include Gir-um-bit NP and State Conservation Area, Karuah NP, Myall Lakes NP, Tilligerry NP, Tomaree NP, Worimi NP, Bushy Island NR, Corrie Island NR, One Tree Island NR and Snapper Island NR.

Total shoreline of Port Stephens is 281km and the vast majority is classed as natural. Mangroves account for 69%, sand 11.7% and cobbles/boulders 7.7%. Artificial foreshore accounts for only 5%. The presence of large areas of healthy seagrass, mangroves and saltmarsh attest to the health of the water ways (see map).

Seagrass communities are one of the most productive and dynamic ecosystems. They provide habitats and nursery grounds for many marine animals, and act as substrate stabilisers. Threats to seagrass are high levels of plant nutrients (agricultural and urban runoff) and reduction of light due to suspended sediment. Boating activity may also stir up sediment and damage seagrass.

The increasing population trends for Australian Pied Oystercatcher and Sooty Oystercatcher, and the recent arrival of Beach Stone-curlew breeding pairs in Port Stephens indicate the local coastal ecosystem remains healthy and is actively managed. However, we should remain vigilant in the face of the many threats.

Neil Fraser has been an active birder for over 25 years and a member of HBOC for over 20 years. He is joint editor of the HBOC journal The Whistler and has a particular interest in shorebirds. Neil participates in regular surveys of the Worimi Conservation Lands section of Stockton Beach and the Gir-um-bit NP at Swan Bay. He also regularly surveys the woodland birds in Mambo Recreational Reserve.

If you missed the first 2 instalments of Neil’s excellent series on the Shorebirds of Port Stephens, you can find them here:

Don’t miss out – see the Shorebird display and activities presented by the Hunter Region Landcare Network at the Sustainable Futures Festival on 11 September in Salamander Bay.

Useful links:

- Port Stephens Estuary Shorebird Site Action Plan, Birdlife Australia/NSW Local Land Services

- Hunter Bird Observers Club

- Hunter Region Landcare Network

- Natural Resources Management, Local Land Services

- Save our Species Program, NPWS

- Threats to Birds, Birdlife Australia

- Migratory Shorebirds Factsheet, Birdlife Australia

- Migratory Shorebird Conservation Action Plan, Birdlife Australia