Shorebirds: The Incredible Journey

This is the second instalment of my three part series featuring the shorebirds of Port Stephens. Here I will discuss the incredible feats of flight and navigation made by these migratory waders as they undertake their lifecycle of living and breeding in a state of constant summer.

During Australia’s summer months, over 1,500 migratory shorebirds are present in Port Stephens, making it the second most important site for these birds in NSW. The most common species are the Far Eastern Curlew, Whimbrel, Bar-tailed Godwit, Pacific Golden Plover, Grey-tailed Tattler and Double-banded Plover. At this time of the year (Autumn), the majority have already departed on the journey to their northern hemisphere breeding grounds.

However, not all birds that spend summer in Port Stephens actually return north. Juvenile birds will ‘overwinter’ here during their first year, returning north to breed in the following northern summer.

Why Do Birds Migrate

Birds migrate to move from areas of low or decreasing resources to areas of high or increasing resources. The two primary resources being sought are food and nesting locations. Birds that nest in the Northern Hemisphere tend to migrate northward in the spring to take advantage of burgeoning insect populations, budding plants and an abundance of nesting locations. As winter approaches and the availability of insects and other food drops, the birds move south. An abundance of high energy food is essential to allow shorebirds to rapidly build up energy reserves prior to making their migratory flights or laying their eggs. More on this below.

Their lifecycle

Most migratory shorebirds in Port Stephens were born in Northern China, Siberia or Alaska. Migration departures from southern shores to the northern breeding grounds are staggered through March until early April. Time of departure is determined by a bird’s destination: birds leaving in early March breed in more southern areas of Northern China, Siberia and western Alaska – while birds leaving later breed further north. Their arrival at the breeding grounds is governed by the clearance of snow cover.

The flight north and subsequent breeding and chick raising activities require large amounts of energy. As well as building up energy reserves prior to departure, birds will rest and recharge enroute, mostly along the mudflats of the Yellow Sea.

On arrival at their breeding grounds, the birds mate and commence egg laying within a few days. Incubation for most species typically takes around three weeks and fledging around four weeks. The chicks of migratory shorebirds are altricial and are able to feed themselves within 24 hours of hatching.

Post-breeding adults and juvenile birds congregate along the northern coastlines for several weeks, building up fat reserves for the southward migration. Adult birds depart prior to juveniles. When juvenile birds arrive at their summer locations, they are around four months old.

By way of example, male Bar-tailed Godwits increase their weight from around 270 gm to over 400 gm prior to departure, while females increase from around 330 gm to over 500 gm. On arrival at the breeding ground, a nest consisting of a lined scrape beneath herbage is constructed and on average, four eggs are laid. Eggs are large, each equal to 11% of the female’s body weight. This highlights the importance of the rest stop in the Yellow Sea for the birds to build up energy reserves prior to egg laying. Incubation takes 20-21 days and fledging 28-30 days. Incubation duty is shared, with the female on the nest during the day and the male at night.

On their non-breeding grounds, they mainly eat bristle-worms (up to 70% of diet) plus small bivalves and crustaceans. In the Yellow Sea, most of their food intake is the bivalve mollusc Potamocorbula laevis, plus lesser amounts of bristle-worms. On the breeding grounds, they consume Crane fly larvae, other invertebrates and some berries.

Their incredible journey

The flight to the summer breeding grounds in Northern China, Siberia and Alaska can be as far as 17,000 km. In preparation for this, birds embark on a feeding frenzy in the weeks prior to departure, building up their fat reserves and increasing body weight by more than 50%. The adult bird’s plumage also changes from unremarkable greys and browns to brilliant reds, oranges, black and white indicating their readiness for reproduction.

So why do the birds migrate to these remote northern locations to breed? Primarily it’s the availability of food. The brief northern summer with its long daylight hours produces an explosion of growth as plants, insects, and fish race to complete their life cycles before autumn sets in. Migratory shorebirds take advantage of this ephemeral bounty to supply themselves with enough food to nest, raise young, and equip themselves with the fat reserves for the long return journey. Insect swarms are so prevalent, adults can feed without interrupting incubation and chicks can feed without leaving the nest site.

The roadmap

The route taken by migratory shorebirds from Australia and New Zealand to their northern breeding grounds is known as the East Asian – Australasian Flyway (EAAF) and is shown on the map at the top of the page. This extends through Papua New Guinea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Vietnam, China, Taiwan, North and South Korea, Japan, northern Russia and across to Alaska. Different species and sub-species may take different routes within the EAAF, depending on their destination, the prevailing weather conditions, the availability of suitable recharging sites enroute and their energy needs.

To successfully make the journey, birds rely entirely on their own internal energy reserves and the assistance they gain from favourable seasonal wind systems. They fly day and night, sleep on the wing and do not land on the water. During the day they fly at altitudes up to 5,000m and at lower altitudes during the night, depending on the prevailing weather conditions. Their flight speed varies from 30 to 60 km per hour.

However, birds generally cannot make the flight direct to their breeding grounds and many species on the EAAF stopover at staging sites in the Yellow Sea to rest and refuel. Others take a more measured journey, stopping over at a number of locations along the flyway.

Master navigators

Birds returning to their breeding grounds are able to unerringly locate the same site they used in previous years. The mechanism they use to navigate is not fully understood. It is known that they use the earth’s magnetic field, sensing it via a protein molecule called cryptochrome 4 that is present in the bird’s eye. This provides an internal compass that allows them to navigate following a previously imprinted pathway. As well as using the earth’s magnetic field, they are also thought to use their acute sense of smell plus visual cues such as landmarks and the position of the sun and stars to find their natal sites.

Tracking migrating birds

Photo © Queensland Wader Study Group

There are two main methods of tracking migrating birds, using either a geolocator or a satellite tracking transmitter. The weight of a tracking device should not exceed 2-3% of a bird’s weight. A geolocator is a lightweight device (around 1gm) used on shorebirds that are too small for a satellite tracking device. It is mounted on a plastic flag attached to a bird’s leg. It records daylight intervals during the bird’s journey. The bird has to be recaptured at its summer site to allow the data to be downloaded. Locations are determined by georeferencing the recorded daylight hours.

Satellite transmitters are attached to larger birds and can be either solar or battery powered. The transmitters are attached to the birds back by a harness that will eventually break, allowing the transmitter to fall off. They weigh around 10gm. This method is very expensive due to the cost of the transmitter and the associated satellite time, but has the advantage of providing the bird’s locations at all times.

The following maps show the extraordinary tracks recorded for a number of species. Click on each map to enlarge.

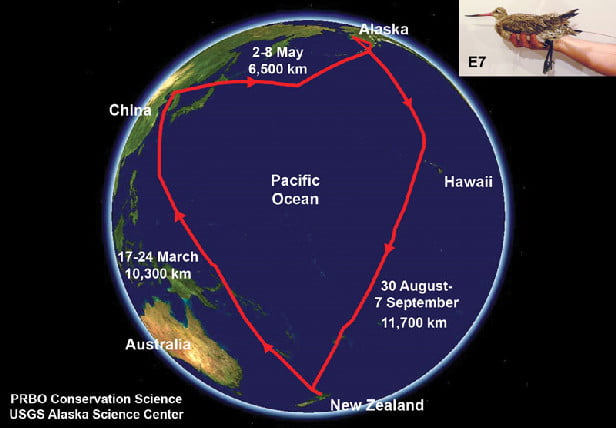

Migration route of Bar-tailed Godwit E7, 2007. Image source

The above map shows the flight path of the now legendary Bar-tailed Godwit named ‘E7’ which was one of 16 birds captured at Miranda on North Island, New Zealand, and fitted with satellite transmitters. E7 departed Miranda on 17 March 2007 and flew 10,200 km non-stop to Yalu Jiang on the Yellow Sea, arriving 24 March 2007. The bird rested and refueled until 2 May 2007 when it again departed and flew non-stop 6,500 km to Alaska, arriving 8 May 2007. After breeding, the bird returned, departing 30 August and flew 11,700 km non-stop across the Pacific Ocean, arriving at Miranda on 7 September 2007. This is the longest continuous journey ever recorded for a land bird. The total around trip was 28,500 km. Bar-tailed Godwits can live for 34 years, which indicates they may cover as many as 1 million km during their lifetime!

Migration route of Bar-tailed Godwits from Roebuck Bay, 2008. Image source

In 2008, 15 Bar-tailed Godwits were captured at the Broome Bird Observatory on Roebuck Bay and filled with satellite transmitters. The birds departed mid-March and surviving birds returned early September. The birds flew directly north to the Yellow Sea with intermediate stops, and after resting and refueling, flew to Northern Siberia to breed. They returned via the same route.

The Bar-tailed Godwits that migrate from Miranda (and Port Stephens) are the subspecies Limosa lapponica baueri, the largest of the Godwits and those from Broome are the slightly smaller subspecies Limosa lapponica menzbieri.

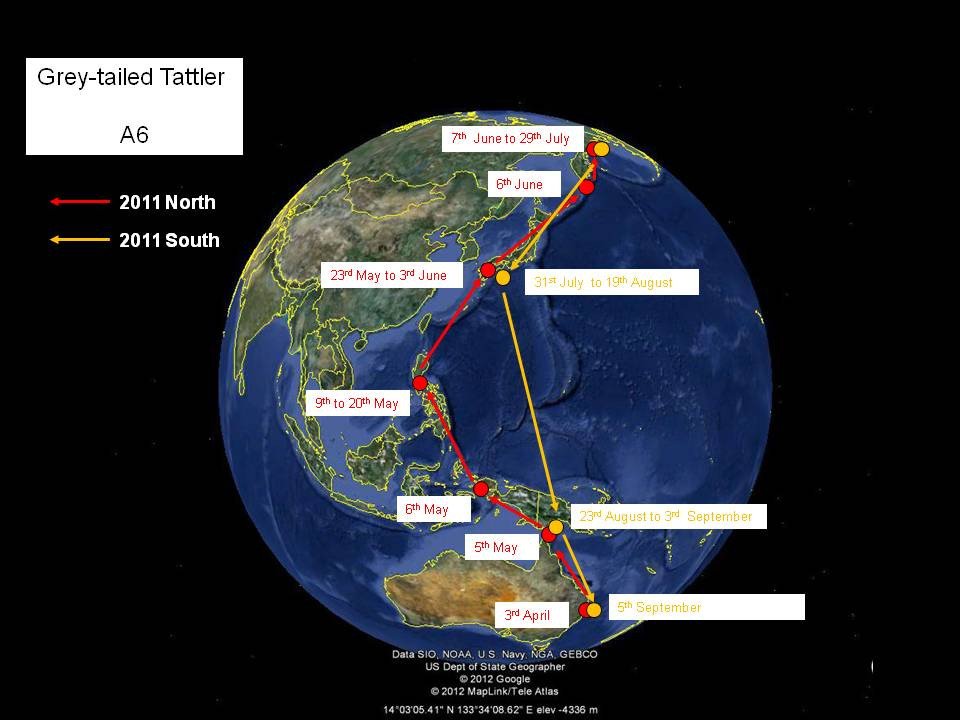

Migration route of Grey-tailed Tattler A6, 2011. Image source

A Grey-tailed Tattler A6 was banded near Brisbane and fitted with a geolocator. The bird departed on 3 April 2011 and flew via staging locations in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Papua, Philippines and Japan, arriving at the Kamchatka peninsula on 7 June. The bird departed the breeding grounds on 29 July arriving back in Moreton Bay on 3 September 2011.

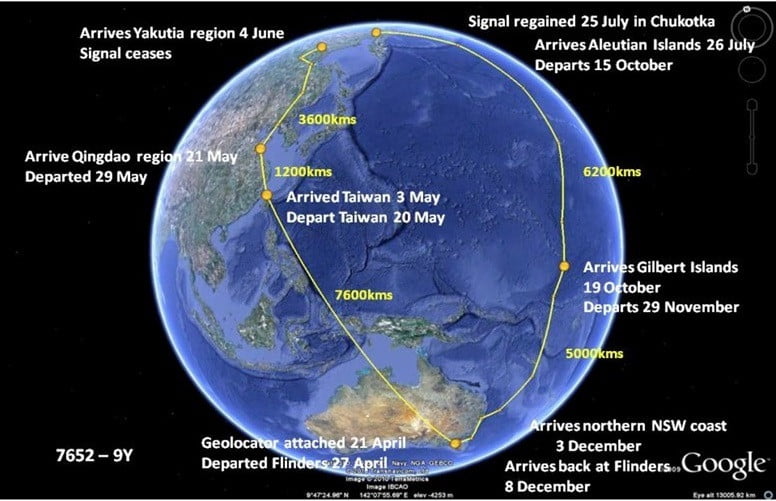

Migration route of Ruddy Turnstone E9, 2011. Image source

The smallest migratory shorebird is the Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres which weighs only 110-130 gm. Ruddy Turnstone E9 was captured at Flinders, Victoria in April 2011 and fitted with a geolocator. It departed on 27 April and flew to Yakutia in northern Siberia via Taiwan and the Yellow Sea, arriving 4 June. It departed for the return trip on 25 July and returned via Alaska and the Gilbert Islands, arriving Flinders on 3 December 2011. The total around trip was 27,000 km!

A New Zealand migrant

A Port Stephens shorebird with a rather different migratory pathway is the Double-banded Plover Charadrius bicinctus. It is a medium-sized dotterel that migrates to eastern and southern Australia from New Zealand during its non-breeding season, from March until August. In Port Stephens they are found around Swan Bay, Corrie Island and Winda Woppa. The birds breed inland at high altitude along the rocky streams on New Zealand’s South Island. After ‘overwintering’ on the beaches of Port Stephens, they return to their breeding grounds using favourable westerly winds in late August. It is the only species of land bird that migrates between New Zealand and Australia and is unique among shorebirds in that it undertakes an east-west migration.

Considering the conditions experienced in the southern highlands of New Zealand over winter, it is easy to understand why the birds would prefer to spend the winter months in the more temperate conditions of our relatively deserted local beaches.

In the next EcoUpdate I’ll conclude this series with a discussion about why Port Stephens is so important to migratory shorebirds, the threats they face and what is being done to protect them. Read the article here.

Useful Links:

- We may finally know how migrating birds sense Earth’s magnetic field – New Scientist

- E7 – a Godwit on a mission

- Tracking a Godwit from Broome observatory

- Watching a Satellite Tracked Godwit depart Roebuck Bay

- Satellite Transmitters and Geolocators – Queensland Wader Study Group

Follow the links below for species profiles from Birdlife:

- Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica)

- Double-banded Plover (Charadrius bicinctus)

- Pacific Golden Plover (Pluvialis fulva)

- Grey-tailed Tattler (Tringa brevipes)

- Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariensis)

- Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)

- Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus)