Are NSW Marine Sanctuaries under threat from new Draft Management Plan?

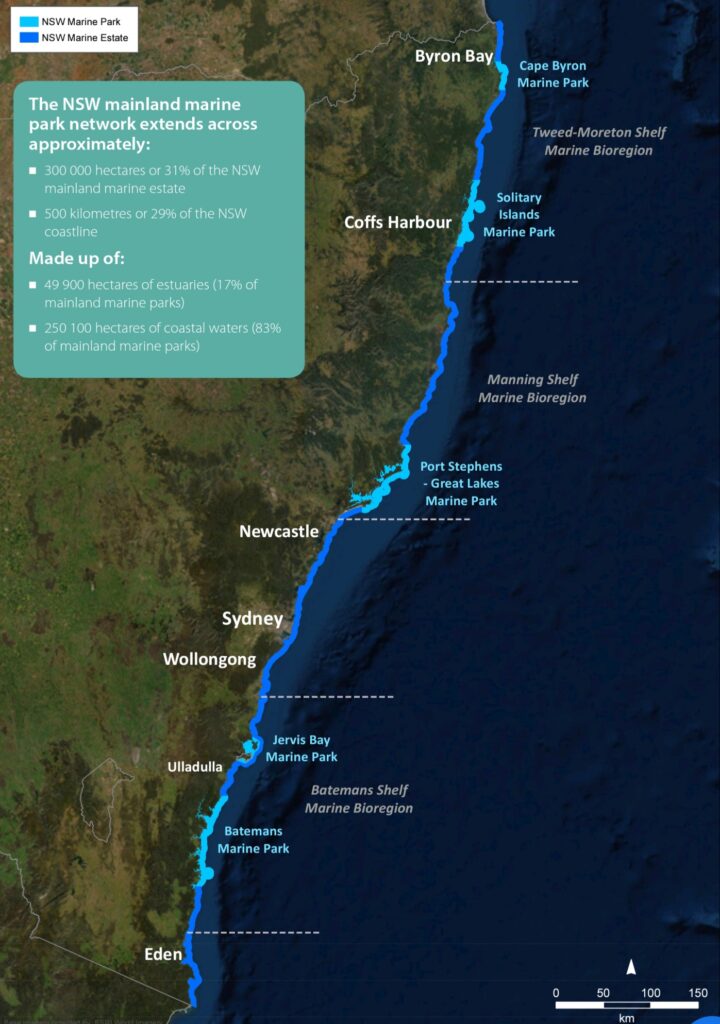

The NSW Government recently released the NSW Mainland Marine Park Network – Draft Management Plan 2021 – 2031 (DMP) for public comment. This is our opportunity to have a say on how our marine parks, including the Port Stephens – Great Lakes Marine Park, should be managed for the next 10 years.

Unfortunately, it appears that the Government has chosen to ignore the advice of its own expert panels and marine scientists. This Plan fails to provide any ambitious conservation goals, operational guidance and is dismantling a system that has been working adequately for many years, with no valid explanation as to why.

The Port Stephens Examiner’s regular feature ‘Beneath the Surface’ showcases the beauty and wonders of the deep. How can we protect it?

The most effective and internationally accepted system to protect key marine environments is through the establishment of sanctuary zones. These are areas within marine parks that provide the highest level of biodiversity and ecological protection and where extraction activities are prohibited. They provide this by:

- allowing the plants and animals to grow to their maximum breeding size thereby keeping the largest individuals in the gene pool.

- protecting key life-cycle stages (breeding, nursery, feeding etc.) for a range of inter-dependent species including fish.

- providing important reference sites for long term research into climate change and fisheries.

- providing socio-economic benefits though tourism, leisure, education and social wellbeing.

- providing ecological insurance against fisheries and environmental management failure.

- safeguarding natural heritage for future generations.

World’s best practice and the Australian Marine Science Association (the peak body) recommends ‘marine parks with 30% sanctuary zone as the most effective and therefore the preferred design option’.

According to the technical paper2 commissioned by NSW DPI on behalf of the Marine Estate Management Authority ‘NSW Marine Protected Areas cover approximately 35 per cent of state coastal and estuarine waters including: 20,000 hectares comprising aquatic components of terrestrial national parks and nature reserves; 12 aquatic reserves covering around 2,000 hectares; and six multiple use marine parks covering approximately 345,000 hectares (MEMA 2017).

Approximately 6 per cent of the NSW marine estate is zoned as highly protected or no-take (i.e. sanctuary zones), equivalent to IUCN protected area category II National Park. The remainder of the estate allows varying levels of extractive resource use and other activities, equivalent to Category IV Habitat/Species Management Area.’

While the DMP does not explicitly threaten sanctuary zones, it does not put forward any meaningful actions to enhance the role of sanctuary zones over the coming 10 years. This will be addressed separately in the rules and regulations for each individual park, which includes reviewing the multi-use zoning system. The sanctuary zones are part of this system and new local rules could introduce proposed ‘low impact fishing activities’ (which are not explained in the DMP) rendering sanctuary zones ‘sanctuaries’ in name only and destroying many years of conservation effort.

NSW legislation requires marine parks management plans to be reviewed every 10 years. Now, after a lengthy 15 years, the proposed DMP heralds a ‘new approach’ which replaces recognised worldwide best practice with a process of threats and risk analysis. But this process lacks the scientific rigour required to judge the success or failure of proposed management actions and no sound rationale has been offered for initiating these changes. It is difficult to see how this ‘new approach’ will improve the management of marine parks.

Another failure of the process is that broad community engagement has been lacking and awareness of this review process appears to be very low with little understanding of how to participate. Furthermore, the release of this document just ahead of the long holiday season makes it even more difficult to gain the attention and response that a comprehensive community consultation process demands.

The legislation governing marine parks in NSW provides sound guidance for their management. It states that the primary purpose of marine parks is to

‘conserve biological diversity and maintain ecosystem functionality and integrity.‘

It also states that marine parks should be managed in ‘a manner consistent with Ecologically Sustainable Development Goals.’ These goals are universal and should underpin the management actions proposed in the DMP. These include the precautionary principle – to ensure that any management action will not cause any further harm and that inter-generational equity ensures that the current or enhanced marine environment is left for the next generation. These principles should be primary considerations for all concerned. Why do they appear to have been side-lined in this once in a decade DMP?

EcoNetwork has requested an extension to the proposed 31 January 2022 deadline for comments so that proper information and consultation can take place in a reasonable timeframe. We are yet to hear back.

The Government recently released two authoritative technical papers that review the results of scientific and socio-economic research on marine parks since 2012.

The scientific review1 shows overwhelming support for sanctuary zones and their unique ability to deliver the most cost-effective and efficient methods for achieving the primary purpose of marine parks. The socio-economic paper2 shows strong community support for sanctuary zones, including by the majority of recreational fishers. So why have the outcomes of both these technical papers been ignored by the new draft Management Plan?

There is a general misconception that marine parks are fisheries management tools. They are not. The DMP acknowledges marine parks and fisheries management have different objectives and that ‘even well managed fisheries have substantial impacts on ecosystem integrity’. Nonetheless NSW marine parks are managed under DPI Fisheries, a case of the fox in charge of the hen-house or at the very least, a conflict of interest. It clearly demonstrates a poor understanding of the role and values of marine parks, which should be managed by a different metric and decoupled from DPI Fisheries.

NSW needs stronger protections for its unique marine environments – EcoNetwork has joined other conservation organisations in calling for something more tangible than just motherhood statements in this ‘marketing plan’.

Read the full Marine Parks Association/EcoNetwork Port Stephens submission here.

To submit your own comments, or using this proforma response we have prepared, you will need to log on to the Department’s website to answer their survey.

This process will guide (and limit) your responses but there is a section you can upload a pre-prepared submission within the survey.

EcoNetwork’s opinion is that the ‘yoursay’ survey method for this review document is inappropriate as it forces simple responses to complex issues. There is no right or wrong answer and results are unlikely to influence decision-makers. So please supplement this by attaching your own comments.

If the online system is too complex, post your submission to: Draft Marine Parks Network Management Plan, NSW Marine Estate Management Authority, Locked Bag 1 Nelson Bay NSW 2315.

Submissions closed on 31 January 2022.

References:

- Evaluation of the performance of NSW Marine Protected Areas; biological and ecological parameters, August 2020.

- Social, Cultural and Economic Science Technical Paper for NSW Marine Protected Areas, August 2021.

Associated documents:

- NSW Marine Park Engagement

- NSW Mainland Marine Park Network – Draft Management Plan 2021 – 2031

- Community Information Webinar 19 January 2022

- Marine Estate Management Act 2014 No 72

- Marine Estate Management Regulation 2017

- Fisheries Management – a mixed bag. September 2021. Iain Watt, marine scientist and President, EcoNetwork.

- The future of our beaches: erosion and artificial reefs. October 2021. Iain Watt, marine scientist and President, EcoNetwork.