The fragile state of the world’s food system

OPINION

by Rob McCann, Sustainability Manager

Few issues highlight the importance of sustainability more than the current food crisis afflicting the world. As we will learn in coming months, we aren’t immune here even in Port Stephens. And like many sustainability issues, in the pursuit of lower prices and profits we have ignored warnings over the years and sleepwalked into a potential catastrophe of our own making.

At this moment, about 45 million people in 43 countries are “teetering on the edge of famine”, said David Beasley, Executive Director of the World Food Programme1. He added that “if we do not address the situation immediately, over the next 9 months we will see famine, we will see destabilisation of nations and we will see mass migration”. This is of course caused in large part by the recent invasion of Ukraine, however there are several other factors affecting food security around the world, and it is likely to get worse as the planet warms2.

Until the invasion, Ukraine and Russia produced and exported (mostly through Ukraine) about 30% of the world’s wheat. As such, the effects from the invasion alone have now plunged an additional 47m people into acute hunger3. The Economist magazine recently dedicated a whole edition to the dire nature of the world’s food security (The Coming Food Catastrophe – May 21st 2022) which I highly recommend (link at bottom of article). This article explains that the impacts from the invasion, inflation, fuel prices, supply chain blockages and other factors are, and have been, amplified by significant weather events, and will worsen due to global climate change. India, another important wheat exporter, was hit with record heatwaves as well as severe winds and hail in February, battering crop yields. When prices also went up, the Indian government in May announced a ban on wheat exports, with a further 26 countries doing the same, in order to secure domestic supplies. Further east, China indicated that last year’s floods mean its winter wheat harvest could be “the worst in history”4. At the moment, the world’s food system cannot cope with any other shocks, not least as a result of climate change which has regional and continental-scale impacts on agriculture.

In Australia, up to 13% of the general population and much as 32% of the indigenous population was already food insecure in 20205, with demand for charitable food relief surging in the same year6. While domestic supplies of food are typically stable in Australia, another shock such as drought or flooding coupled with the inflation we are seeing would make for a sobering situation at home for many indeed. Our food often needs to be transported long distances by road, which further exacerbates price increases as the cost of petrol and diesel continues to rise. We also have a very highly concentrated food market dominated by Coles and Woolworths. You will hear nauseating remarks like “we have no choice but to pass on costs to consumers”, while at the same time a quick google search will reveal that Woolworths net profit margin is up 476%, while Coles has netted over $1b.

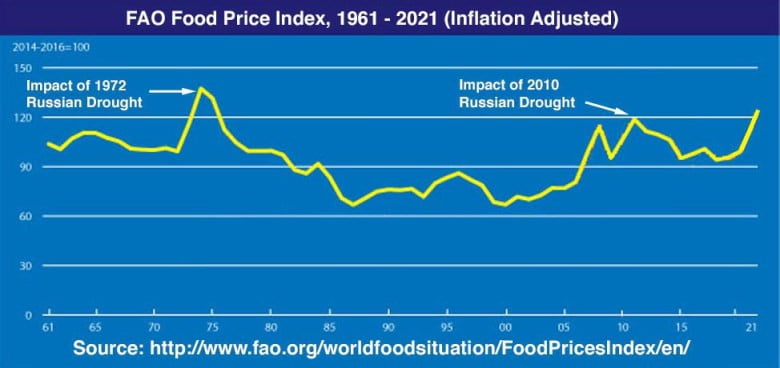

While the WFP and other organisations have made significant headway in improving food security over the years, the multitude of factors happening at once is too much for any organisation or national government to handle. The fact is we remain simply terrible at planning ahead for volatility, and we are having the entirely wrong conversations about such critical issues. While the invasion of Ukraine surprised most, the same can’t be said for the ensuing food crisis. Indeed, a drought in Russia alone can cause food prices to spike globally. This has happened at least twice; once in 2010 and once in 1972, as shown above, and caused conflicts in various parts of the globe such as Africa. It is no surprise that conflict has had such a large effect on food prices.

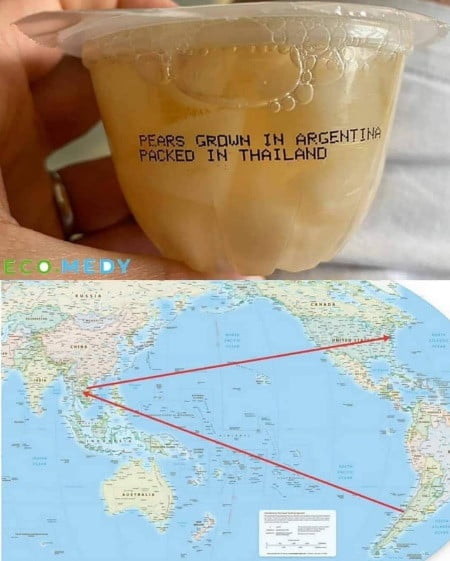

Despite all this, it may surprise some that we often have more than enough food to feed the world, even though about 30-50% of food is wasted7,8 and much of the world’s base food commodities are kept for biofuels or cattle feed. “This is not a food shortage crisis as much as it is a distribution crisis”, said Dr. Martin Frick recently, the Director the World Food Programme Global Office in Berlin9. In an attempt to avoid a catastrophe, central banks around the world have printed extraordinary amounts of money into the system, making the labour market, supply chains, prices and real value almost impossible to make any sense of, and now has affected food. Over the decades in Australia we have caused the slow death of the local farming market, small farming cooperatives, vegetable gardens and the like. We have become increasingly dependent on a fragile network of long distance supply chains, and commodity markets over which we have practically no control (see photo on the right for example). And on top of all of this, we are compromising soil, nutrients, water, and the entire climate which 7.8 billion people depend on for food. All this has battered our food resilience and puts us all in a very precarious position if nothing is done about it.

In another article I will dive into some solutions that are readily available around the world. For now though, it is now more important than ever to buy locally where you can, grow your own food if you have the means, and as a society start treating food like the valuable essential that it is.

Useful links:

- A ring of fire is circling the globe, sparking starvation, mass migration and destabilization, warns WFP Chief | World Food Programme

- The World’s Food Supply is Made Insecure by Climate Change | United Nations

- AMIS Market Monitor – Global food security consequences of the war in Ukraine

- The coming food catastrophe | May 21st 2022 | The Economist

- Understanding food insecurity in Australia | Australian Institute of Family Studies

- Food Bank Hunger Report 2022

- 30% of food is wasted. Worldwide food waste | ThinkEatSave

- Almost half of the world’s food thrown away, report finds | Food | The Guardian

- Dr Martin Frick – World Food Programme interview ABC

- WildAware – “Pears grown in Argentina, packed in Thailand.